This story fpreviously aired on Oct. 31, 2015. It was updated on June 22, 2024.

Produced by Judy Rybak and Peter Henderson

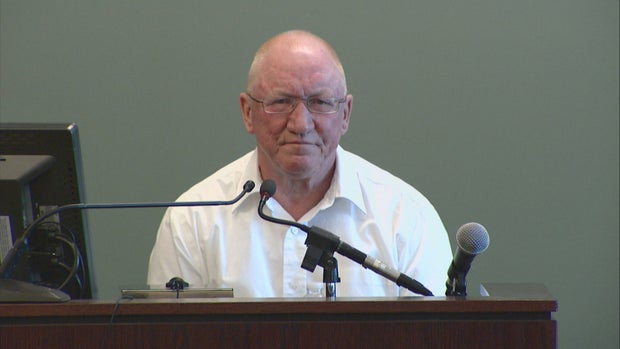

It took almost every ounce of strength left in his 85-year-old body to get to the witness stand, but Bill McCabe waited 43 years for this day and the start of this trial in January 2013.

Prosecutor: Good morning, Mr. McCabe … do you remember September 27th 1969?

Bill McCabe: Yes, sir.

Prosecutor: How old was John at that day?

Bill McCabe: He was 15 years, six months and two weeks.

“I always visualized him as being a big shot somewhere. John Joseph McCabe. ‘My son, JJ,’ you know?” Evelyn McCabe told “48 Hours” correspondent Richard Schlesinger. “But I never got to see any of those things.”

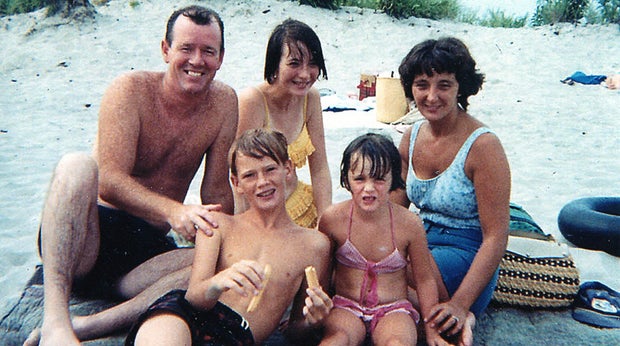

In the fall of 1969, two men had just landed on the moon, thousands had just crashed at Woodstock and John McCabe, 15 years, 6 months and 2 weeks old, was living with his family in Tewksbury, Massachusetts.

“I think we have a right to be proud of him,” said Bill McCabe.

Evelyn McCabe

John’s father, Bill, was an engineer. His mother, Evelyn, worked at the school library. His sisters, Roberta, who was 6, and Debbie, who was 17, remember a brother who was always busy, doing what brothers do.

“It was pretty interesting. You open the closet door, and your closet’s filled with grasshoppers,” Debbie recalled with a laugh.

“I just remember his hands were always dirty, like, with oil or grease or a frog in his hand,” said Roberta.

“He brought home a goose once too?” “48 Hours” correspondent Richard Schlesinger asked Evelyn.

“Oh yeah, Canadian goose, big sucka!” she exclaimed.

“It’s fun to watch you talk about this cause your eyes light up. I mean you have fond memories of those days,” Schlesinger commented to Evelyn.

“Oh yeah,” she replied.

Evelyn holds on to any reminder of her son.

“I have John’s money,” Evelyn said. “I — I can’t spend it.”

“And you’ve had it all these years?” Schlesinger asked.

“Yeah, 45 years,” said Evelyn.

“Do you take it out a lot?”

“Every now — every now and then I — the smell’s gone off of it now,” she chuckled as she smelled the cash in her hand. “I almost put it in the casket with him. And then I thought, ‘No, I’ll just keep it with me. And when I see him again, I’ll give it to him.'”

When she last saw John on Sept. 26, 1969, Evelyn gave him permission to go to a dance at the Knights of Columbus Hall.

“Took a shower, scrubbed his hair, put his father’s aftershave on. He didn’t shave but he put his father’s aftershave on. Oh yeah, he got all spruced up,” Evelyn recalled.

“I let him go. I let him go out the door. I shouldn’t have,” she said.

“Eleven o’clock, I started looking out the window,” Evelyn continued. “That’s when the dance closes. He should be home by midnight. So I went down to the dance and checked the road, screaming out the window. John! John! …No John. … I started prayin’ at that point.”

The next day, police came to the house and took Evelyn’s husband to the basement to talk.

“They didn’t want me to know anything,” she said. “But I heard them.”

Evelyn got on her knees and pressed her ear to a vent in the bathroom.

“This is where I could hear everything that was going on down cellar,” she said kneeling on the bathroom floor as she did all those years ago.

The police were telling her husband John’s body was discovered by three young kids cutting through a vacant lot in the neighboring gritty city of Lowell.

“I heard that he was tied up. And there was tape on his eyes, on his mouth. I heard a lot,” Evelyn told Schlesinger. “I cried. I lay there and cried.”

A huge investigation was launched by the Lowell, Tewksbury and Massachusetts State Police.

Gerry Leone was the local D.A. who years later took on the case. Today he’s a partner in the law firm, Nixon Peabody.

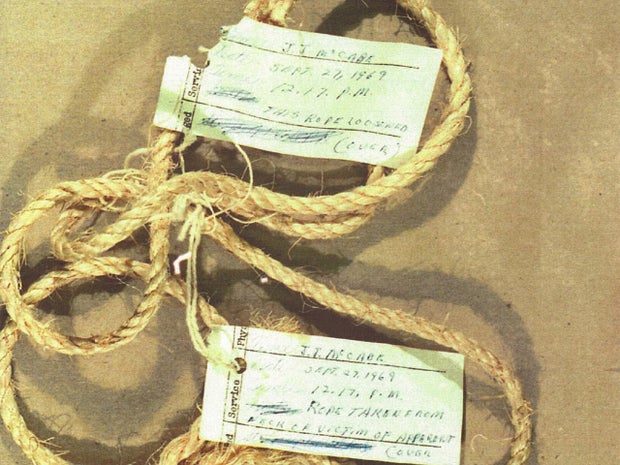

“What evidence did they collect at the scene?” Schlesinger asked Leone.

Middlesex County D.A.’s Office

“The rope that was used to tie John up … Tape that was used to tape his eyes and mouth. All of his clothing and his shoes,” he replied. “There was forensic evidence, but it wasn’t really meaningful because you couldn’t tie it to anyone in particular.”

But the case looked promising at first. A witness had spotted a car near the crime scene that night.

“And I believe the way he had described it was a 1965 Chevy Impala, colored — plum or maroon,” said Leone.

Then another tip led police to a schoolmate of John’s — 16-year-old Mike Ferreira, who says he barely knew John.

“I probably seen him like a handful of times in my life. I didn’t really — he wasn’t a friend,” said Ferreira.

Ferreira and his friend, Nancy Williams, were questioned because they had picked John up when he was hitchhiking, on his way to the dance.

“I picked him up and gave him a ride to the corner and I never saw him again,” said Williams.

Ferreira told police that while the dance was under way, he left Williams and met up with his best friend, Walter Shelley.

“Me, Walter and Bob Ryan took a ride to Lowell tryin’ to get some beer,” he said.

They were in Walter Shelley’s car. It was maroon and it was a 1965 Chevy Impala. Police searched it, but found no evidence.

Still, Walter Shelley was now a person of interest. He was brought in for questioning and later polygraphed five times. The tests showed he was “lying in all vital areas of the questioning.”

“If you read the reports,” Leone explained, “now you start seeing Ferreira and Shelley, Shelley and Ferreira.”

Ferreira was questioned multiple times.

“I knew where they were goin’, I mean, I’m not totally stupid,” he said.

But Ferreira wasn’t helping himself. At one point while joyriding with some friends, he suddenly blurted out that he killed John.

“Yeah you know, I was 16. We were drinking’ jokin you know … ‘Yeah I did it.’ They knew I was jokin,” Ferreira said. “I was a joker.”

Leone says police were not amused but there was no way to corroborate what Ferreira said.

“Without physical evidence, without a witness statement putting him at the scene … The Ferreira lead kept drying up,” said Leone.

There were dozens of other people the police investigated — other teens, local drug dealers and pedophiles. Detectives worked the case hard for two years. The whole time, Bill McCabe worked on a record of his son’s life.

“I wasn’t tryin’ to be an author or anything like that. I —I was just lookin’ at ways to hold on to him … keep his memory,” he told “48 Hours.”

Bill McCabe also tried to make sure the police never forgot his son.

“I was always on the phone talking to the police. I’d be up in the middle of the night. She’d be saying, ‘what the hell are you doing up? Get back to bed,'” he said.

Despite Bill’s persistence and the intense police effort, there were no arrests.

“Shelley and Ferreira went into the service in 1970. So the following year, the two of them left the area,” said Leone.

And the McCabe family was left without any answers … for decades.

A COLD CASE HEATS UP

With each passing season, John McCabe’s case grew colder, but his mother kept asking the most painful questions about how he died.

“I tried to strangle myself just to visualize what it felt like,” Evelyn McCabe said. “I wondered … ‘Did he call for me? What kind of a mother was I?’ I wasn’t there for him.”

For a time, Evelyn set a place for John at the dinner table. His absence was a constant presence in the house.

Evelyn McCabe

Through it all, Bill McCabe continued to write John’s story, while constantly pushing police for an ending.

“You can’t just do something wrong and not have to pay for it…” he said.

The case stalled for some 30 years, until November 2000, when Jack Ward, a childhood friend of John’s, made good on a decades old promise to Bill.

“He would say, ‘Jackie, have you heard anything about John?'” Ward said. “‘You keep your eyes out and let me know.’ And I says, ‘If I ever hear anything, Mr. McCabe, you know, I’m gonna tell you.'”

Ward had been at a cookout at a house in Tewksbury, where he ran into a kid from the old neighborhood, Mike Ferreira.

“We’re all sitting around drinking and that’s when he just blurted out…” Ward said. “‘I know who killed John.’ And he said it to me again. … ‘I know who killed John.’ And, you know, finally I said, ‘Who?’ He says, ‘Walter.’ I said, ‘Walter Shelley?’ He says, ‘Yeah.'”

“And I said, ‘what would be Walter’s motive to kill John?’ He said, ‘Marla … because of Marla,” said Ward.

Ward said Marla Shiner was Walter Shelley’s girlfriend back then. But he said the trouble was that Shiner also seemed to like John McCabe, and by all accounts, Walter Shelley was one very jealous young man.

Ward admits he sat on the information for a while, worried about how to tell Bill McCabe.

“You go knockin’ on somebody’s door and say, ‘Hey — I know who killed your son,’ you better have it right,” he said.

“I was shocked when he told me,” said Bill.

“So I scribbled it on a piece of paper and I put it in the Bible … on a page, beginning the book of John so I wouldn’t forget it. … And I immediately called the police,” said Bill.

But it took many more calls from Bill McCabe and three more years for police to show up at Ferreira’s door. It was now 2003. Ferreira worked as a forklift operator and lived in Salem, New Hampshire. Nancy Williams, his friend back in the day, was now his wife.

“Mike wouldn’t hurt a fly. Never … I know. He wouldn’t,” said Nancy Ferreira.

Mike Ferreira says he remembers the cookout conversation with Jack Ward very differently.

“Jackie went and told them I said Walter Shelley killed him. I never said that,” Ferreira said. “And at this cookout, you know, I already had a few drinks and he’s runnin’ his mouth, ‘Shelley did it, Shelley did it.’ And this went on all afternoon. …And finally I got sick of hearin’ it. I says, ‘He probably did it.’ Next thing I know, three years, four years later, I got the cops down at my house wantin’ to talk to me about John McCabe.”

Ferreira also denies discussing the jealousy motive with Ward.

“That’s his theory. I never said that,” he said.

But again there was no corroborating evidence. So again, the case stalled.

“What did they tell you about the investigation?” Schlesinger asked Evelyn.

“‘It’s going fine.’ It was always going fine,” she replied.

“And how long did they tell you that?” Schlesinger asked.

“And you know what, it was sittin’ on a frickin’ shelf,” said Evelyn.

But the police had not forgotten John McCabe. In January 2007, 37 years after the murder, Gerry Leone was sworn in as Middlesex County District Attorney.

“The Lowell Police Department took it upon themselves to visit me weeks after I’d been elected to say, ‘We’d actually like you to focus on this one and take a hard look at it with us,'” said Leone.

Investigators had gone back over the files and a name jumped out at them in Mike Ferreira’s latest interview with police. In recounting the night of the murder, Ferreira said he was with Walter Shelley, but this time he added a name and said “the other guy” with them was Alan Brown.

“Edward Alan Brown’s name surfaces as someone who we’re gonna focus on,” said Leone.

Edward Alan Brown was 17 and lived not far from the McCabe’s when John was killed. He had long since moved away, but when police tracked him down he said he knew nothing about the murder — never even heard of it.

“So how likely is it that he would never even have heard of the murder of John McCabe in a town the size of Tewksbury,” Schlesinger asked Leone.

“I’d say curious at the time,” he replied.

And police got a call from Brown’s wife that was even more curious.

“His wife … told police that she thought he was lying,” Leone said. “Carolyn Brown indicates to police that 20 to 25 years earlier her husband had told her about an evening … where he was involved in a young man being killed.”

But even that wasn’t enough. It was the same old story. There was no corroborating evidence and no real movement in the case until 2011, when Det. Linda Coughlin was assigned to find the killers.

“You think this case really took off when you met Detective Linda Coughlin,” Schlesinger noted to Evelyn.

“Yes, definitely,” she replied.

Asked why she felt that way, Evelyn said, “Because of her attitude. She … she said, ‘I’m going to get them.’ And she did.”

Detective Coughlin zeroed back in on Edward Alan Brown. He was retired from the Air Force and living in New Hampshire.

Coughlin interrogated Brown – just twice. When Brown learned he failed a polygraph he suddenly broke down. He confessed that he was there when Walter Shelley and Mike Ferreira killed John McCabe.

Lowell police brought in the McCabe’s and told them Brown’s story about John’s final hours.

“Why?” Roberta McCabe asked. “My dad started crying, he keeled over on the table…”

On April 15, 2011, nearly 42 years after John McCabe’s body was found in a vacant lot, his father’s perseverance finally paid off.

“Mr. McCabe held our feet to the fire, he never let us forget John McCabe’s murder,” Lowell Police superintendent Ken Lavallee told reporters.

Lowell Police Department

The D.A.’s office announced the indictments of Edward Alan Brown for manslaughter and Michael Ferreira and Walter Shelley for first-degree murder. Two names known to police since day one; two names also gathering dust in John’s book of mourners.

“The murderers came to the wake. And they came to the funeral,” said Evelyn.

SECRETS REVEALED

It would take almost two years to bring the men accused of killing John McCabe to trial. Two more years the McCabe’s would have to wait.

On Jan. 18, 2013, Edward Alan Brown was called to testify against his one-time friend, Mike Ferreira — the first defendant to go on trial.

For the first time, Brown publicly shared the details of the night John died. Brown says he was at home watching television when Mike Ferreira and Walter Shelley pulled up to his house:

Edward Alan Brown: They wanted me to go with them to help them.

Prosecutor: Help them do what?

Edward Alan Brown: I didn’t know at the time until I got in the car and we left.

Brown testified they were on their way to the Knights of Columbus Hall when he learned of their plan:

Edward Alan Brown: They said they wanted to go find this kid that had been… uh you know, messing around with Marla to teach him a lesson.

Prosecutor: And how did you know Marla Shiner?

Edward Alan Brown: It was Walter’s girlfriend.

Edward Alan Brown: Michael noticed John McCabe was thumbing. And he said, “There he is.” … And we pulled up next to John, Michael got out and grabbed him and pushed him … in the back seat where I was…

Michael was facing back — at John, tryin’ to — to smack him. And John had his arms up to try to — to stop him from doing that. … We went under the Spaghettiville Bridge …

Brown says they drove up a dirt road to the vacant lot and pulled over:

Edward Alan Brown: And we got him outside the car.

Prosecutor: Who pushed John out of the car?

Edward Alan Brown: I did. …I thought they were just gonna slap him around.

Prosecutor: What happened next? Then Michael and Walter wrestled John, tripped him up, and got him on the ground.

48 Hours

Brown testified that he and Shelley held John McCabe down, while Ferreira tied him up:

Edward Alan Brown: Michael tied his ankles, then went around and tied his — wrists together. Then he took another piece of rope … around his ankles and attached it up to his neck. …they had put tape on his mouth. John’s — squirming, wiggling, trying to get out. … He’s lying on his belly … uh, with his legs up in the air and his — his head turned sideways.

Then they said — that, “This — this’ll teach you to — to mess with Marla anymore.” And we got in the car and left.

Brown says they drove around drinking beer for a while:

Edward Alan Brown: Then — I told ’em we should go back and let him go…

Brown says they eventually returned to the lot:

Edward Alan Brown: Michael and Walter got out of the car and went over to him. They were there for about 30, 45 seconds … and they came quickly back to the car … we started to drive off and one of ’em said that he wasn’t breathing.

John McCabe had died of strangulation.

“I wonder … I wonder what he thought of that night,” Evelyn McCabe said, taking a deep breath.

Edward Alan Brown: Then they brought me home.

Prosecutor: What did you do?

Edward Alan Brown: I don’t remember. I think I cried.

Brown says he kept the murder a secret for 41 years because he was afraid of Michael Ferreira:

Edward Alan Brown: Michael said, “If anybody talks to anybody about this, I’ll kill him.”

“Alan Brown’s a friggin’ liar, and I mean, they know that,” Ferreira said. “According to the prosecutor, he’s been to Iraq and Afghanistan five tours. Maybe he’s got somethin’ wrong in his head.”

“They talk about these people that give false confessions,” Nancy Ferreira said. “Either he did it with somebody else or by himself, or he is really a messed up human being.”

Eric Wilson, Michael Ferreira’s attorney, believes that police pressured Edward Alan Brown because he was someone they could force into confessing to a crime he did not commit. They also offered him a deal: no jail time.

“My sense of Edward Brown was he was easily led,” Wilson told Schlesinger. “Edward Brown did not walk into Lowell Police Department headquarters and say, ‘Look, I got to get this off my chest.’… After being … interrogated by trained detectives … he was faced with the threat of spending the rest of his life in jail — or he could tell the police what they wanted to hear.”

“The question that I had to answer for the jury is why would he tell them that if he didn’t do it,” said Wilson.

“Did you think you could do that? That’s a tough sell,” Schlesinger noted.

“It was a tough sell – but Ed Brown gave me a lot to work with,” Wilson replied.

Over the course of two days, Ferreira’s attorney grilled Brown relentlessly until he admitted that the prosecution had fed him parts of his story:

Eric Wilson: You were fed information it was a dirt lot, right?

Edward Alan Brown: Yes.

Eric Wilson: You were fed information that it was near a railroad tower, right?

Edward Alan Brown: Yes.

Eric Wilson: And you’re being told that Shelley was jealous over Marla Shiner, right?

Edward Alan Brown: Yes.

“There are certain pieces of information that an investigator may provide to someone who they’re interviewing to see whether or not they know anything about that, to see whether or not it jogs their memory,” said Gerry Leone.

“Well, but — couldn’t that also be a way of telegraphing to the witness what you want him to say?” Schlesinger asked.

“Well, in this case that didn’t have to happen, because … Brown was the one who talked about the rope, the tape, the binding of John,” Leone replied.

However Brown got his story, Wilson claims it cannot be true, because it does not fit the evidence. In fact, in the 1969 police reports, detectives noted that they were “unable to find any evidence of a scuffle.”

“There was no suggestion anywhere around John McCabe’s body or the scene that that struggle described by Edward Brown ever took place,” said Wilson.

“Why would Edward Alan Brown lie and implicate himself so directly in what happened unless it was the truth?” said Leone.

Wilson thought it was not enough to try to discredit Brown — he also had to punch holes in the alleged motive: jealousy over a girl. He’ll do it by calling that girl, Marla Shiner, to the witness stand.

MARLA SHINER TAKES THE STAND

Prosecutors had a problem. It was their star witness, Edward Alan Brown, who seemed to wither under strong cross examination from the defense:

Eric Wilson: Mr. Brown, you’ve lied under oath when you’re scared, right?

Edward Alan Brown: Yes.

Eric Wilson: You’ve lied under oath when you’re nervous, right?

Edward Alan Brown: Yes.

Eric Wilson: You’ve lied under oath when you’re frightened, right?

Edward Alan Brown: Correct.

Eric Wilson: You still can’t get your facts straight, can you?

Edward Alan Brown: No.

So prosecutor Tom O’Reilly called Det. Linda Coughlin to counter accusations that she’d forced Edward Alan Brown to confess and fed him details:

Tom O’Reilly: At any point did you feed him information as to the investigation?

Det. Coughlin: Never.

But Eric Wilson says Coughlin also had tunnel vision and ignored evidence of other suspects:

Eric Wilson: There were a number of investigative reports and material that you either overlooked or didn’t even know about, true?

Det. Coughlin: I don’t know what you’re referring to.

Eric Wilson: How about Richard Santos?

Richard Santos was flagged in a Tewksbury police report as a suspect in the McCabe murder in 1974. Santos was arrested for committing a crime eerily similar to John McCabe’s murder.

“This young woman was abducted on Route 38,” Wilson said. “Her feet were bound, her hands were tied behind her back, her mouth was duct taped, and her eyes were taped shut.”

“All of the facts that surround Santos as a possible subject lead you to be suspicious,” Former D.A. Gerry Leone explained. “But there was never anything tying him to motive, opportunity, means.”

Still, the judge allowed the jury to hear about Santos and another suspect: Robert Morley, a local 25-year-old, who reportedly knew both Ferreira and Shelley, and was suffering from mental illness:

Eric Wilson: He was labeled … long before you were assigned this case, as a strong suspect, right?

Det. Coughlin: There is a report that uses the word for him, “strong suspect”. In the very same report, mentions Mr. Ferreira as a prime suspect.

But it’s how Morley became a strong suspect that makes him so interesting. Police learned about him shortly after the crime from his own brothers.

“Morley’s own brothers went in and said that they thought he might’ve been involved in it,” Schlesinger noted to Leone.

“Yeah … they thought he might have,” he said.

Leone says Morley’s brothers were mistaken.

“I think what happens in matters like this is people will say, ‘Sure, you should take a look at X or Y because they have a profile of somebody who would do something like this and they were around the area at the time.’ But then you have to look at the evidence and see whether or not the evidence leads you to believe that they had anything to do with it,” said Leone.

Eric Wilson: Did the brothers have any specific evidence that you’re aware of?

Det. Coughlin: They did not.

“He split to Florida the day after he was questioned by police,” Wilson explained. “Mr. Morley — years later … committed suicide.”

Eric Wilson: you learned of his death, suicide right? He jumped off a bridge, right?

Det. Coughlin: His brother says he fell off a bridge.

The defense also tried to punch holes in the alleged motive for the murder and called a surprising witness to do it: Marla Shiner, the girl who Walter Shelley and Mike Ferreira allegedly killed for.

48 Hours

Edward Alan Brown had just testified that Shiner was Shelley’s girlfriend in September of ’69 and Shelley was jealous because John McCabe was flirting with her. But Shiner says John never flirted with her:

Defense: Did you ever go to a dance with John McCabe?

Marla Shiner: Never.

Defense: Was it ever conveyed to you that he had any type of romantic interest in you in August or September of 1969?

Marla Shiner: None.

The McCabe’s say it doesn’t matter if the flirting was real or imagined.

“She could have been — just stopped and said hello to John, and Shelley could have walked by and seen it … and he’s gonna explode,” Bill McCabe told “48 Hours.”

Next Marla Shiner threw the prosecution a curve ball:

Prosecutor: September 26th, 1969 were you dating Walter Shelley?

Marla Shiner: No … I was not dating Walter – when John McCabe died.

Prosecutor: When did you start dating him then?

Marla Shiner: I believe it was after that death.

Prosecution: How old were you?

Marla Shiner: 13.

Prosecution: You were 13 in September of 1969.

Marla Shiner: Oh I don’t know I can’t do the math right here.

But according to police, Shiner told them she was dating Shelley at the time and was just 12 years old when they started seeing each other:

Prosecutor: You didn’t tell the police that you were dating Walter Shelley in 1969 when John McCabe was killed?

Marla Shiner: I — no — I don’t believe I did tell them that.

“Why lie about dating someone, unless it was because of her that John was murdered,” said Roberta McCabe.

“48 Hours” had questions for Marla Shiner too, but she declined our request for an interview. Shiner eventually married Walter Shelley, but it didn’t last. She said he was “very violent.”

Asked by the assistant district attorney if Walter Shelley was a jealous man, Shiner said, “Absolutely.”

48 Hours

This was a hard fought trial until the end. And then it was up to the jury to decide: did Mike Ferreira help Walter Shelley kill John McCabe over a girl? Or was Edward Alan Brown telling the story the prosecution wanted to hear? It only took jurors five hours to decide.

“I told Michael that we had to hope for the best but be prepared for the worst. And — he was ready for that,” said Wilson.

For the McCabe family, more than four decades of waiting and working came down to this moment.

“What did you think the verdict was gonna be?” Schlesinger asked Evelyn McCabe.

“Guilty. My God, he was guilty. If for no other reason, he was there,” she replied.

“It’s hard to understand how the jury could, you know, anticipate otherwise,” said Bill McCabe.

Bill McCabe was too nervous and too sick to sit in the courtroom that day, so he waited in another room while Evelyn and their daughters heard the verdict: Not guilty.

Everyone, including Mike Ferreira was so stunned, it took a while to sink in.

“When the verdict came in, when you heard that — that Ferreira had been acquitted -” Schlesinger said to Evelyn.

“I had to go tell my husband that,” she said.

“Were you afraid to tell him?”

“Yes,” said Evelyn.

Asked why, she told Schlesinger, “I was afraid he was gonna die.”

Tragically, Evelyn was right. Just four days after the verdict, Bill McCabe’s heart gave out — and he gave up.

“What do you think killed your husband?” Schlesinger asked Evelyn.

“Stress. The stress of the trial,” she replied.

While Evelyn McCabe laid her husband to rest next to their son, the D.A.’s office had a decision to make. After losing the case against Mike Ferreira, would it go ahead with the trial of Walter Shelley?

JUSTICE FOR JOHN?

“I still don’t believe Bill is gone. I can still hear him snore in the night. And then I feel the bed. He’s not there,” said Evelyn McCabe.

She was determined to honor her husband’s dying wish.

“He laid in the hospital bed, and I said, ‘I’ll pick up and take over for you,'” said Evelyn.

She’d see to it that someone would pay for John’s murder.

“And my father just kept prayin’ and sayin’ to me, ‘Before I die, we have to find out who did this,” said Roberta McCabe.

And watching Michael Ferreira go free was tough for some jurors, too.

“So, how hard was it for you to acquit him?” Richard Schlesinger asked juror Michael Duquette.

“It was very difficult,” he replied.

Duquette said the biggest problem was Edward Alan Brown.

Asked if the majority of the jurors believed him, Duquette told Schlesinger said “No. …They just felt that he was not telling the truth.”

“They felt that he had been fed information,” Duquette continued. “And that didn’t make a ton of sense to me. Maybe he wasn’t the best witness. But I just can’t see somebody saying, ‘I did it,’ when they didn’t do it.”

Duquette came to believe Brown and wanted to find Michael Ferreira guilty of something. But the only choices the jurors had were first- and second-degree murder.

“So what did you want to convict him of?” Schlesinger asked Duquette.

“Manslaughter. And it wasn’t an option,” he replied.

Despite the Ferreira loss, prosecutors decided to try to convict the other suspect in the murder: Walter Shelley.

“The acquittal in the Ferreira case didn’t do anything to lessen our belief that we had the right people who were responsible for killing John McCabe,” said former D.A. Gerry Leone.

September 3, 2013, seven months after Michael Ferreira’s acquittal, it was Walter Shelley’s turn to stand trial. Shelley was 17 the night of John’s murder. He’s now 61, remarried, and has lived quietly in Tewksbury ever since — just a few miles from Evelyn McCabe.

If convicted of first-degree murder, Shelley could spend the rest of his life in prison.

It was the same case prosecutors presented against Michael Ferriera. The same motive and the same evidence presented by the same witnesses: Marla Shiner, Det. Linda Coughlin, and once again, the state’s star witness, Edward Alan Brown.

“Was it any easier to sit through the second trial?” Schlesinger asked Roberta McCabe.

“No, I wanna say it was harder,” she replied. “Dad wasn’t there for backup.”

Brown seemed less rattled this time, more confident. And the McCabe’s allowed themselves to hope.

“I can keep my fingers, my toes, everything crossed,” said Roberta.

During closing arguments, the defense called Brown a liar.

“He’ll tell you whatever you want to hear,” the defense attorney Stephen Neyman told the court.

But the prosecution argued that Brown would never implicate himself in a crime he did not commit.

“What’d he confess for? He was talked into it?” prosecutor Tom O’Reilly said in his closing.

The week-long trial went to the jury. This would be the McCabe family’s last chance to see someone held accountable for killing John.

“We had faith that the jury was gonna come with the right answer this time,” said Debbie McCabe.

Finally, two days later, a verdict.

Walter Shelley’s wife and family waited nervously. Evelyn McCabe couldn’t bring herself to even sit in the courtroom and had to wait outside.

“She couldn’t hear another ‘not guilty,'” Debbie said. “She was scared she was gonna drop dead.”

48 Hours

Guilty and life behind bars for Walter Shelley, whose knees buckled upon hearing the verdict. This jury believed Brown.

“So when you heard ‘guilty,’ do you remember the first thing you thought?” Schlesinger asked Roberta McCabe.

“I thought my father would be proud,” she said. “We got one of them.”

It was the final twist in a mystery filled with them. For the same crime and on the same evidence, one man walked free and one man went to prison.

48 Hours

“John, guess what? We got him. … Billy, it turned out beautifully,” Evelyn told her son and husband at their graves. “Please John, please take great care of him till I get there, please? And then I will.”

He didn’t live to write about it, but Bill McCabe finally got the end he was looking for to the story he wrote about John’s life and death. A story that took four decades to play out about his boy who will be 15 years, six months and two weeks old … forever.

Michael Ferreira pleaded guilty to perjury and was sentenced to probation for 5 years as of June 7, 2021.

Because Walter Shelly was a juvenile at the time of the murder, his conviction was downgraded to second degree murder and he will be eligible for parole after serving 15 years in prison.

Evelyn McCabe died in August 2016. Her wrongful death suit against Ferreira, Shelley and Brown is being pursued by John’s sisters. It is still pending.